A Parent’s Guide to Science Projects

We all want to make sure that our children do well in their science classes. This is especially the case when the matter of science fairs comes up. Science projects can be a rather daunting task for most children, mostly because it requires a great deal of initiative and a more advanced application of concepts. Not only does your child need to come up with a suitable project that’s easy to research, they must rigorously follow a process to the letter to come up with a suitable project. Unless you’re blessed enough to have a child who’s exceptionally gifted in the sciences, or otherwise unusually diligent for someone their age, chances are they’ll need your help somewhere along the way.

Unfortunately, not all parents immediately grasp the finer aspects of assisting their children with their schoolwork. What often happens is that the parent ends up doing most of the work, with the child taking all the credit. Naturally, this is a little unfair. It might be a little unfair to you, as your work won’t be acknowledged, but it’s also unfair to children who may have done more of the work themselves. Most importantly, it’s unfair to your child — you rob them of their chance to learn something.

So the trick is to strike that balance where you’re assisting enough that your child isn’t struggling, but not so much that it turns into your science project.

Remember Your Priorities

Remember, the goal is not to flatter anyone’s egos. If you’re pushing your child to “win” a science fair, then you’ve already lost sight of the point of it. The whole goal is to get your child to start thinking scientifically and to apply the scientific method, not win a ribbon. So, ironically, trying to win may hamper your efforts to do so. No one is looking for the biggest, flashiest or most complicated project. They’re looking for the most scientific one.

It’s actually possible for a project that technically “failed” — here meaning a hypothesis set out has been disproven by the experiment — to win first place. But only if the project follows the scientific method accurately enough.

Remember always: the goal is not to win. The goal is to learn. So whatever project you and your child choose to pursue, make sure this goal always receives priority.

You Are Not in Charge

The most important thing to remember is that this is your child’s project. By all means, offer advice and act as a sounding board. Throw out ideas and see what they like. If a project seems unrealistic or difficult, then feel free to steer your child towards something more attainable. You can even help out with particularly fiddly or big parts if you wish. But you should, as much as possible, resist the urge to take over.

It is always your child’s project. It is not, never has been, and never should be yours.

If at any point during the project your child is sat in one corner doing nothing, you’re doing it wrong. Ideally, it should be you sitting in the corner doing nothing.

You do not set off the model volcano. Your child does. You do not stand at the table during the fair. Your child does. You do not write out the conclusion, the experiment results, or the premise. You don’t even draft it.

Always make sure your child is center stage, and always make sure that they do the bulk of the science project. Otherwise, you’re just robbing them of their chance to learn and shine. More damningly, you are robbing them of their self-respect and esteem. Because what does it say to the child if it seems like their parent can’t trust them with a project that apparently has their name on it?

Your Role Supporting Your Child

Your role, therefore, is not to do the work, except in such cases where your child cannot safely operate. It is worth noting that preventing injury to your child during a particularly exciting project absolutely is your role — reality-check the project and perform any unsafe tasks yourself. And as always, be prepared for any accidents with first-aid, a cell phone, and the locations of emergency rooms or pediatric urgent care centers like Night Lite.

So let’s say, for instance, that your child wants to demonstrate the application of solar energy. Your job in that instance is to find books, DVDs and websites that help explain solar energy in ways the child is likely to understand so they can research the topic. Say during the planning stage your child suggests that they’re not sure what to do for the project. Feel free to throw in ideas. If your child is lagging, give them pick me ups. Reward them when they achieve milestones, and encourage them to keep going until they finish. Suppose your child, at the science project’s conclusion, isn’t sure what to write. While you should not write anything yourself, you can suggest things and help them brainstorm.

In the ideal project, your presence is barely even noticed. If the science project is a film, you’re one of the sound crew, the scenery directors, or even one of the go-fers. Intervene only as much as you need, and always remember it’s your child who’s supposed to be learning here. All you need to do is enable that.

About the author:

Christian Mills is a freelance writer and family man who contributes insights and advice into the blessings and challenges of parenthood and familiy living.

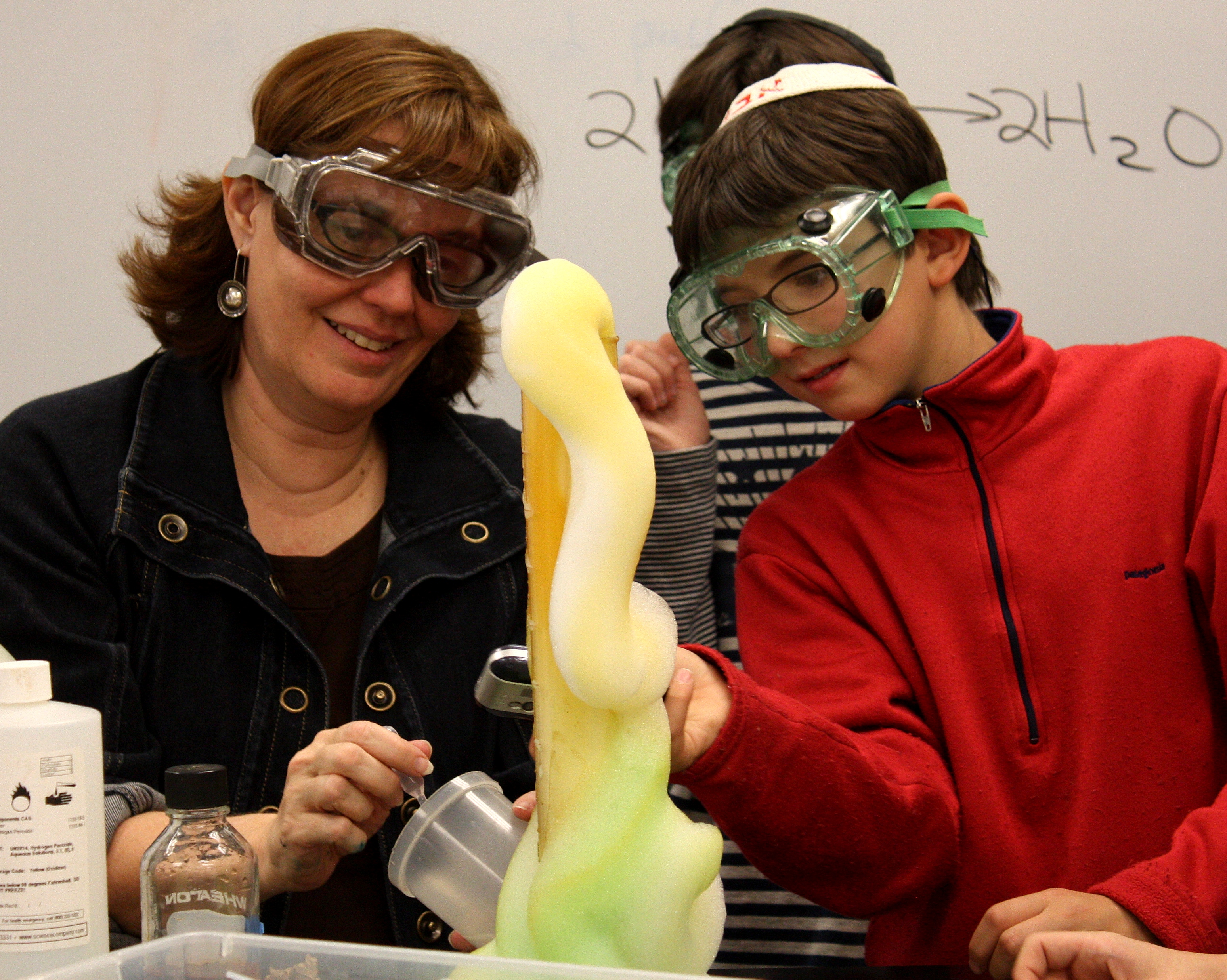

Photograph by eigenadam, sourced from Wikimedia Commons

My grown son help his son with his projects. I love watching them they work great together and have fun doing it.